Optogenetics is a groundbreaking field in neuroscience that combines optics and genetics to control the activity of individual cells within living tissue. By utilizing light to manipulate the function of genetically modified cells, optogenetics has revolutionized our understanding of brain function and has vast potential in the treatment of neurological disorders. While much of the work has been conducted in animal models, research in humans is beginning to emerge, with remarkable implications for both understanding the brain and advancing therapeutic interventions.

Understanding Optogenetics

Optogenetics involves the use of light to control cells within living organisms. Specifically, researchers introduce genes that encode light-sensitive ion channels into the target cells. When exposed to light of specific wavelengths, these channels open or close, altering the electrical properties of the cell. This allows for precise, real-time control over neuronal activity. The light-sensitive proteins used in optogenetics are typically derived from microorganisms such as algae or bacteria. A well-known example is Channelrhodopsin-2 (ChR2), which responds to blue light and allows for the rapid depolarization of neurons.

In a typical optogenetics experiment, researchers implant optical fibers into the brain or other tissue of a living organism. These fibers can deliver light to specific regions, activating or inhibiting neurons with remarkable precision. The ability to manipulate neuronal activity in this way has provided scientists with unprecedented insight into the brain's circuitry, and it has opened up exciting possibilities for therapeutic applications.

Optogenetics in Neuroscience: A Tool for Understanding the Brain

One of the primary uses of optogenetics is to unravel the complex workings of the brain. Neuroscientists use optogenetic tools to activate or silence specific neurons or neural circuits to study their role in behavior, cognition, and disease. In animal models, optogenetics has been instrumental in providing evidence for causal relationships between neural activity and behavior. For example, researchers have used optogenetic techniques to map brain regions involved in memory formation, decision-making, and emotion regulation. These experiments have demonstrated that specific neural circuits play crucial roles in processes such as learning, addiction, and stress.

In addition to enhancing basic neuroscience, optogenetics has also provided insights into neurological disorders. Conditions such as Parkinson's disease, Alzheimer's disease, epilepsy, and depression are linked to disruptions in specific neural circuits. Optogenetics allows researchers to manipulate these circuits directly, shedding light on how they malfunction in disease states and helping to identify potential therapeutic targets.

Optogenetics in Humans: Advancements and Challenges

While optogenetics has been an invaluable tool in animal research, its application to humans is still in its early stages. However, the field is advancing rapidly, and clinical studies are beginning to explore its potential in treating neurological and psychiatric disorders.

1. Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders

Parkinson’s disease is characterized by the degeneration of dopamine-producing neurons in the brain, leading to tremors, stiffness, and difficulty with movement. One of the key regions of the brain affected by Parkinson’s is the basal ganglia, a group of structures involved in movement control. Recent research has explored the use of optogenetics to modulate the activity of neurons in the basal ganglia to alleviate symptoms of Parkinson’s disease.

In preclinical studies involving animal models of Parkinson’s disease, optogenetics has been used to stimulate or inhibit specific neurons within the basal ganglia to restore normal movement patterns. Early results suggest that optogenetic modulation of brain activity could offer a promising therapeutic strategy for Parkinson’s disease. If these findings can be translated to humans, optogenetics could provide a way to enhance motor function and reduce symptoms in patients suffering from Parkinson’s.

2. Epilepsy

Epilepsy is a neurological disorder characterized by recurrent seizures. These seizures occur due to abnormal electrical activity in the brain. Optogenetics has shown promise as a potential treatment for epilepsy by providing a means of precisely controlling the firing of neurons in the brain to prevent seizures. In preclinical models, optogenetic techniques have been used to silence overactive brain regions that contribute to seizures, reducing the frequency and severity of epileptic events.

Researchers are now working to develop safe, targeted methods of delivering optogenetic therapies to human patients with epilepsy. This could involve the implantation of light-delivery devices directly into the brain, allowing for real-time control over neuronal activity. The potential for optogenetics to provide a highly targeted and personalized treatment for epilepsy is exciting, as it could significantly reduce the need for traditional pharmaceutical therapies, which often come with side effects.

3. Vision Restoration

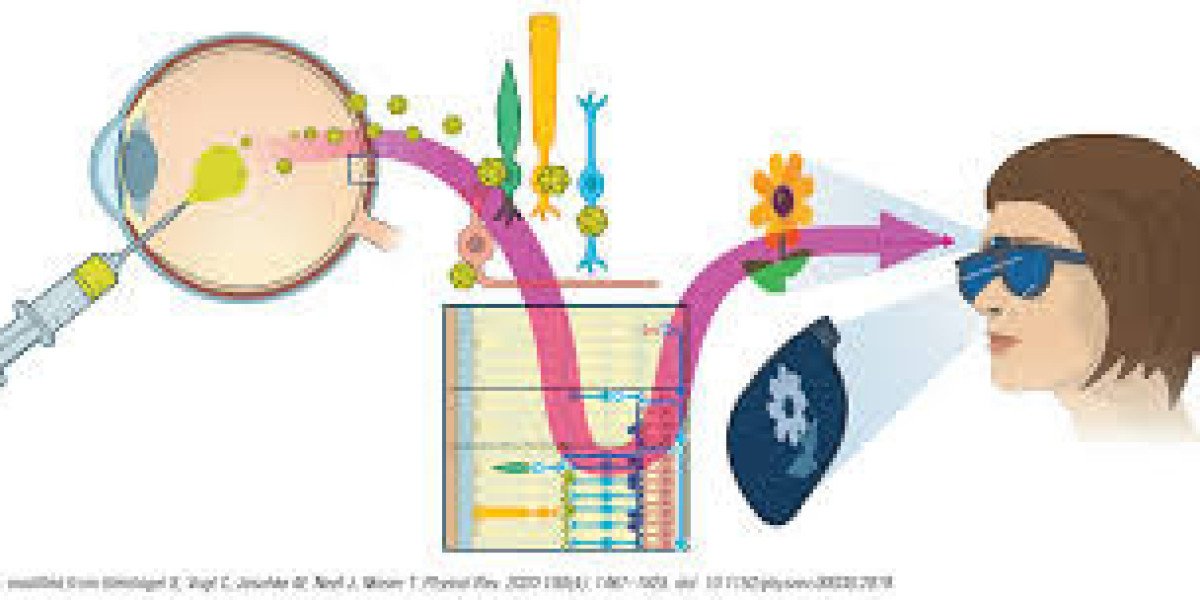

Perhaps one of the most exciting potential applications of optogenetics in humans is its ability to restore vision in individuals with certain types of blindness. Retinal diseases such as retinitis pigmentosa (RP) and age-related macular degeneration (AMD) lead to the progressive degeneration of photoreceptor cells in the retina, resulting in blindness. In some cases, the rest of the retinal cells remain intact, but the photoreceptors needed to convert light into electrical signals are lost.

Optogenetics offers a potential solution by introducing light-sensitive proteins into the remaining retinal cells, effectively "reprogramming" them to respond to light. This approach has shown promise in animal models, where optogenetic therapy has enabled blind animals to regain some level of vision. Clinical trials are currently underway to test optogenetic treatments in humans, and early results have shown that some patients may experience restored light sensitivity, providing hope for future therapies to treat blindness.

4. Psychiatric Disorders

Mental health disorders such as depression, anxiety, and schizophrenia are believed to involve disruptions in brain circuits responsible for mood regulation, cognition, and behavior. In animal models, optogenetics has been used to manipulate these circuits and observe how alterations in neural activity affect behavior. For example, optogenetic stimulation of the prefrontal cortex has been shown to alleviate symptoms of depression in rodents, suggesting that this brain region plays a critical role in mood regulation.

Though still in the experimental phase, optogenetics holds promise as a potential treatment for psychiatric disorders. By directly modulating the activity of specific neural circuits, optogenetic therapies could provide a more targeted and effective treatment option compared to conventional medications, which often have widespread effects on the brain and come with significant side effects.

Ethical Considerations and Challenges

Despite its immense potential, the application of optogenetics in humans raises several ethical concerns. The most significant issue is the invasive nature of optogenetic interventions. Implanting optical fibers and other devices into the brain carries inherent risks, including infection, tissue damage, and unintended effects on surrounding neural circuits. Moreover, the long-term effects of optogenetics on brain function and behavior are not yet fully understood, and further research is needed to ensure the safety and efficacy of these therapies.

Another ethical challenge concerns the potential for misuse of optogenetics in the context of human enhancement. As optogenetics allows for precise control of brain activity, there is concern that this technology could be used for non-medical purposes, such as altering personality traits or enhancing cognitive abilities in ways that may raise moral and societal questions. The regulation of optogenetics, particularly in the realm of human applications, will need to strike a balance between fostering innovation and ensuring that ethical boundaries are respected.

Conclusion

Optogenetics is poised to revolutionize the field of neuroscience and open up new avenues for the treatment of neurological and psychiatric disorders. While the application of optogenetics in humans is still in its infancy, early research in conditions like Parkinson’s disease, epilepsy, blindness, and psychiatric disorders shows great promise. As the technology continues to evolve, optogenetics could become a powerful tool not only for understanding the brain but also for developing targeted, personalized therapies that could dramatically improve the lives of patients suffering from a range of debilitating conditions.

However, the challenges associated with the invasive nature of the technology and the ethical implications of its use must be carefully considered as we move forward. If these hurdles can be overcome, optogenetics may well represent a transformative step toward more effective, precise, and individualized medical treatments in the future.